It’s ‘Either/Or’ for Two Common Gut Microbiome Genera, and Switching Teams Is Tougher Than Expected

isbscience.org/news/2020/05/29/gut-microbiome-barrier/

isbscience.org/news/2020/05/29/gut-microbiome-barrier/

It is increasingly clear that the human microbiome — the trillions of microbes that live in and on us — directly affects our health.

In findings published in the journal PNAS, ISB researchers highlight the dichotomy between two common gut microbiome bacterial genera — Bacteroides and Prevotella. Humans who have a lot of one in their gut tend to have very little of the other, and vice versa.

By repeatedly measuring microbiomes from individuals over time, the team found that there appear to be barriers preventing an easy transition between Bacteroides– and Prevotella-dominated gut communities. Bacteroides-prevalent microbiomes have been associated with a Western-style diet, which includes processed foods and significant amounts of meat and dairy. Prevotella-prevalent microbiomes have been associated with hunter-gatherer diets and people in developing parts of the world where fruits and vegetables are the major sources of sustenance.

“A deeper understanding of microbiome dynamics and the associated variation in host phenotypes furthers our ability to engineer effective interventions that optimize wellness,” said Dr. Nathan Price, ISB professor and associate director, co-leader of the Hood-Price Lab, and co-corresponding author of the paper.

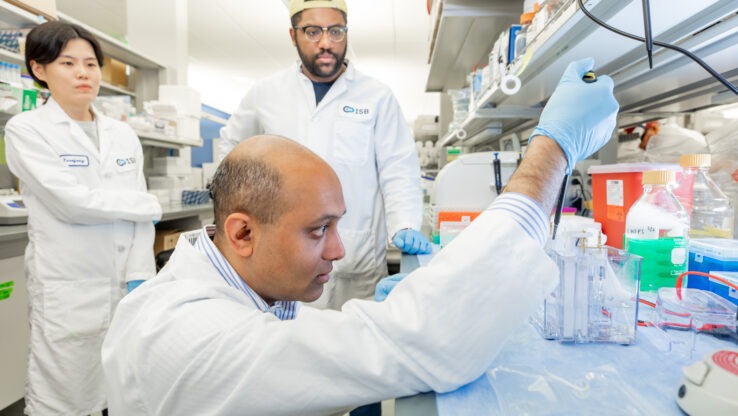

In this study, ISB researchers examined and analyzed the gut microbial makeup of 101 individuals over a one-year timespan, along with clinical markers and serum metabolite profiles.

These findings provide clues for how to further study microbial communities in humans. “An implication from this research is that interventions seeking to transition between Bacteroides– and Prevotella-dominated communities will need to identify permissible paths through ecological state-space that circumvent this apparent barrier, and this is likely to be a feature of many other transitions as well,” Price said.

ISB researchers have recently published other important papers relating to the human microbiome. One paper published in the journal Nature Biotechnology shows the ability to predict the diversity of an individual’s gut microbiome by examining metabolites in the blood, and a paper in the journal mSystems details a new open-source modeling software package that helps pin down exactly how the ecological composition of an individual’s gut influences how the ecosystem actually functions.

ISB Assistant Professor Dr. Sean Gibbons discusses what is possible — and what isn’t — when it comes to changing our microbiomes.