‘Fantastic Opportunity:’ ISB’s Scholars Program Offers Transformational Experience for Ambitious College Grads

isbscience.org/news/2018/01/30/isb-systems-research-scholars-program-college-graduates/

isbscience.org/news/2018/01/30/isb-systems-research-scholars-program-college-graduates/In the summer of 2017, the world’s brightest researchers studying the world’s deadliest infectious disease gathered in the rolling hills of Tuscany, Italy, at the Gordon Research Conference on Tuberculosis, which takes place every two years.

“It’s the kind of environment where you find yourself walking through the countryside with a very pleasant hiking companion only to find out later that day that she’s a MacArthur Genius and a professor at MIT who helped create a whole area in chemical biology,” said Abrar Abidi, who attended the event this past June.

Abidi, pictured below, was invited to present his research at the seminar portion of the conference. “I made dozens of friends there with postdocs and professors young and senior from around the world, who I remain in touch with.”

At 23, Abidi was easily the youngest researcher in attendance. His experience in Lucca, Italy – about 50 miles west of Florence – was the culmination of his tenure as the first-ever awardee of the Systems Research Scholars Program (SRSP) at the Institute for Systems Biology.

SRSP is a two-year, fully funded training program for recent college graduates, and is designed to help transform exceptionally talented and ambitions post-baccalaureate students into the next generation’s pioneers of interdisciplinary research.

Searching for greatness

ISB is currently accepting applications for potential scholars. Applicants must have a degree in a STEM field, prior research experience, a faculty nomination, and a demonstrated interest in pursuing a Ph.D. degree. The application deadline is March 2, 2018.

“We are looking for exceptional young scientists who think independently and want to hone their skills to help build a strong foundation for graduate studies and a life at the forefront of scientific research,” said Dr. Nitin Baliga, senior vice president and director at ISB.

Baliga also served as mentor to Abidi. “Nitin is the mentor people dream of. He has given me opportunities that would make most other young scientists at this early stage in their careers turn green with envy,” Abidi said. “I know that when I go off to graduate school next fall, the dominant question I will ask myself as I seek out a new advisor will inevitably be, ‘Who here most reminds me of Nitin?’”

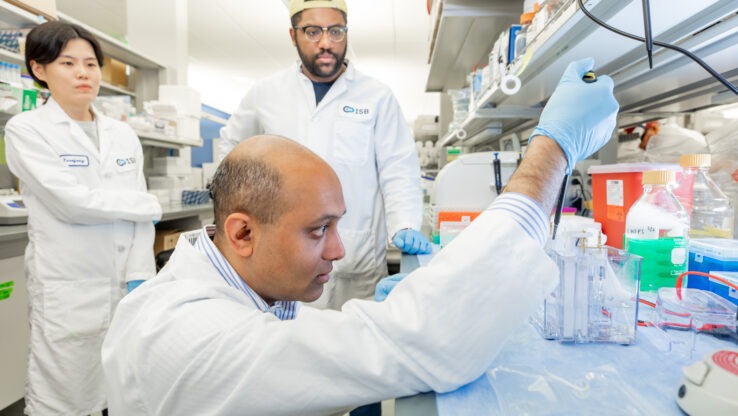

As a systems research scholar, Abidi has studied Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MTB), which causes tuberculosis. This bacterium doesn’t typically start to kill immediately. Upon infection, a person’s immune system detects and responds to the pathogens by deploying cells to surround them and wall them off. “The bacteria have evolved ingenious ways of remaining alive, even in this extremely hostile environment, by slowing or shutting down many of their biological functions,” Abidi said. In this state – called latency – MTB is largely invulnerable to most antibiotics. “They sit there and play dead until some other illness, such as HIV, distracts the immune system. Then they suddenly wake up, start replicating, and attack the lungs, leading, if untreated, to a devastating, painful death for the infected human.

“We understand extremely little about how MTB enters into and emerges from its latent state. My project is to understand the genetic circuitry underlying those transitions,” he said.

Abidi hopes his research will inform the design of new drugs. “This systems approach to infectious disease is extremely different from how most drugs are found, where the pathogens are bombarded with thousands of random molecules, and the ones that kill the bacteria go on to become drug candidates, often with little understanding of how or why they work in the context of the organism of the whole,” he said. “What we’re trying to do is much more rational and deliberate – using our models to predict ways to directly sabotage MTB’s adaptive program, and then testing those predictions in the lab.”

Forming roots in biology

Abidi graduated from Reed College in 2016, and came from the world of physics, not biology. “I was drawn by the boldness of ISB’s vision,” he said, “which is nothing less than to tackle the most challenging, daunting questions in biology in the 21st century.”

Failure and patience are two elements Abidi has come to understand. “Science takes time, and much of that time is spent failing,” he said. He has learned that mature scientists take stock of their mistakes and rarely repeat them, and that biology often consists of long, iterative processes of trial and error before getting results that illuminate – or destroy – a hypothesis or model. “As Nitin sometimes tells me, ‘Biology is where beautiful hypotheses go to die.’ But now and again, despite the provocations and insults of new data, a hypothesis survives, and then you know you’ve discovered something special.”

ISB’s Systems Research Scholars Program is built for aspiring scientists looking for an opportunity to learn in a creative, cross-disciplinary and independent setting.

“This is a fantastic opportunity. Could I go back, I would do it all over again,” Abidi said of the program. “Come to ISB if you are ambitious and eager to deeply engage yourself in a difficult problem at the edge of biological research.”