ISB Engineer Hopes to Save the Sword Ferns in Seattle’s Magnificent Forest

isbscience.org/news/2017/06/20/paul-sword-ferns/

isbscience.org/news/2017/06/20/paul-sword-ferns/

Seattle’s Magnificent Forest at Seward Park is located within one of the nation’s most diverse neighborhoods. The 98118 zip code in southeast Seattle is home to people of all socioeconomic classes including groups of immigrants who speak more than 60 languages. Seward Park serves as an urban oasis for the community to enjoy nature, easy hikes, and access to the expansive Lake Washington. The park’s Magnificent Forest, so called because it contains some of Seattle’s oldest trees, is home to nesting eagles, trillium, woodpeckers, owls, and numerous other creatures.

Read the Seward Park Sword Fern Die Off Blog

For the past two years, volunteer researchers from the University of Washington and Washington State University, ecologists from Seattle Parks and Recreation, and volunteers from Friends of Seward Park have been studying an unexplained and unprecedented die-off of the native sword fern (Polystichum munitum). The die-off has spread radially at 10 meters per year and now covers 12 acres, or more than 10 percent, of this remnant old-growth forest. The death and decline of the sword fern, a hardy and resilient species that dominates the understory in Pacific coast lowland forests from Alaska to California, reflect ecological events that may have local and regional consequences.

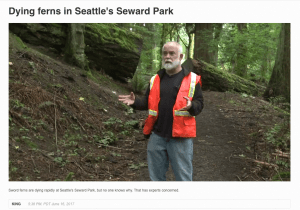

Paul Shannon, who is a senior software engineer in the Price Lab at Institute for Systems Biology and the forest steward at Seward Park, and his colleague Tim Billo, an ecologist from the University of Washington, recently were featured in a segment on KING 5 News. They reported on the drastic die-off of the sword ferns in Seward Park. The die-off is unexplained and swaths of the forest floor are exposed and vulnerable.

Paul Shannon, senior software engineer in the Price Lab at Institute for Systems Biology, volunteers as the forest steward at Seward Park, where sword ferns are dying at an alarming rate.

What’s going to hold the soil in place?

The health of this forest community is intimately connected to the health and happiness of the surrounding human community. Climate change, drought, and urban pollution could be opening a window for opportunistic organisms, including invasive pathogens that could be detrimentally affecting the sword fern population. WSU plant pathologists and renowned fern experts agree that the die-off is grave and novel. Our preliminary data suggest that the die-off is still in the initial stages, currently limited to a few acres in Seward Park. Given the rate of spread, it is unlikely we are anywhere near the end of the spread of the die-off. It may be a harbinger of a more widespread regional threat.

The dramatic and tragic die-off of sword ferns potentially is setting off a series of consequences, including the loss of recreational aesthetics, alterations in water flow and erosion patterns, and cascading effects to other trophic levels that are dependent, directly or indirectly, on sword fern cover.

For more info, contact: Paul Shannon