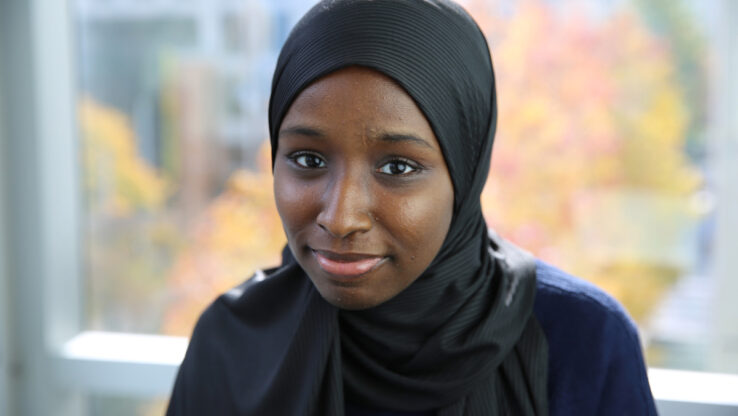

Spotlight on Caroline Cannistra, ISB Systems Research Scholar

isbscience.org/news/2019/07/24/spotlight-on-caroline-cannistra-isb-systems-research-scholar/

isbscience.org/news/2019/07/24/spotlight-on-caroline-cannistra-isb-systems-research-scholar/

Caroline Cannistra joined ISB in 2018 as a Systems Research Scholar. In this Q&A, Cannistra describes her experiences at ISB, research interests, future aspirations, and much more.

ISB: How has your experience as a Systems Research Scholar at ISB been so far? What have you learned through your collaborations with Drs. Jim Heath and Ilya Shmulevich, and members of the Heath and Shmulevich labs?

Caroline Cannistra: Working at ISB with Drs. Heath and Shmulevich has been a unique and enriching experience so far. The nature of the project I’m working on — and ISB’s research environment — is highly collaborative and supportive, and I’ve learned so much just by being in the building, talking with my colleagues, and attending group meetings.

ISB: What projects are you working on?

CC: I’m working on developing a multi-scale spatial model of the immune microenvironment in glioblastoma (GBM), and how it responds to treatment with surgery and checkpoint inhibitors such as the anti-PD-1 drug Keytruda. An ongoing clinical trial is investigating the efficacy of treatment with Keytruda before and after the tumor is surgically removed. We’re using the results of this trial, public GBM datasets, and literature to develop a virtual version of the tumor and the localized immune response. This can be used to formalize our knowledge of this system, or even as a tool in personalized medicine if our model accommodates modifications based on data from individual patients.

ISB: You obtained a bachelor’s degree in bioengineering and applied mathematics at the University of Washington. How would you describe your undergraduate studies compared to your SRSP appointment here at ISB?

CC: In my first few years of undergrad, I worked in the Shou group at Fred Hutch on a project in stochastic modeling of yeast social dynamics. Later on, for my capstone, I developed software to evaluate the evolutionary stability of engineered strains of E. coli through metabolic modeling. The common thread is that I’ve only worked on single-cell organisms before coming to ISB, where I’m currently studying human tissue from a clinical trial. Working with this kind of data is incredibly humbling, and gives me a new appreciation for the urgency of GBM research.

ISB: How do you explain what you do to your grandparents (or people in your life without a science background)?

CC: These days, I talk about 2018 Nobel laureates in medicine and their work in identifying and targeting immune checkpoint inhibitors for cancer treatment. My usual explanation goes something like: “Cancer suppresses the immune system, and Keytruda blocks one of the ways cancer can do that. We’re studying how this works in brain cancer, which has an unusual local immune system.” I describe multi-scale spatial modeling as “virtual experiments” in a lot of different contexts.

ISB: What are your plans following this two-year scholarship?

CC:I’m planning on applying for graduate school while I’m here, but I’m also considering working full-time for Biocellion, the start-up that develops the software I’m using to build the GBM model and run simulations. I spent the past year working for Biocellion on a part-time basis, and the company is starting some very exciting work with companies that produce lab-grown meat. I’d love to get involved with this project if I get the chance.

ISB: Where do you see yourself in 10 years?

CC: I’m not really sure! I think I’ll probably end up pursuing a long-term career in academia, but I’m not sure what that will look like. My interests tend to shift a lot, so I could end up going into a completely different field, or I could start doing wet lab experiments instead of just computational work, or I could end up in industry. As long as I can access the feeling of wonder and curiosity that I get from learning something new, I’ll be happy.

ISB: What do you do when you’re not at ISB? Any hobbies, passions, interests?

CC: For the past 13 years, I’ve been a big fan of knitting. If you come by my desk at ISB, you’ll probably see whatever I’m knitting at the moment. It’s a good way to pass the time during my commute, and translating a pattern to a finished product encourages a way of spatial thinking. A developer of neural networks recently trained a neural network on thousands of knitting patterns and released a collection of patterns generated by this network, and wrote an article about how knitting a pattern is a lot like compiling source code into an executable, observing that knitters would read the network-generated patterns and “debug” them in order to make them usable.

ISB: What is the last book you read?

CC: The last novel I’ve read is “Head On” by John Scalzi, which is part of the “Lock In” series. The series examines a near future where an epidemic leaves one percent of the human population unable to move their bodies on their own, or “locked in,” and most of the affected people navigate the world in robotic bodies they can control remotely with their minds. There’s a lot of exploration of what it means to be disabled, especially in the U.S., and how society responds to people inhabiting artificial bodies in their day-to-day life.

In terms of nonfiction, I’m reading “Clean Meat” by Paul Shapiro, which was released earlier this year and recounts the history of lab-grown meat and cellular agriculture (which includes production of things like leather and silk with in vitro methods). There have been a lot of developments in the industry since it was released, but it’s still really interesting.

ISB: Any hidden skills you’d like to share?

CC: Before I went to college, I used to compete in various math contests with my friends. I would spend most of my time studying all sorts of recreational math topics, which has carried over to some of the higher-level concepts in the work I do now. Sometimes I still look up AIME problems from the Art of Problem Solving website and see if I can solve them.

ISB: Anything you’d like to add?

CC: It’s a pleasure to be here!