What does ISB mean to you?

Innovative Scientific Breakthroughs. Investigating Science Boldly. Inventing Superior Biotech. Isn’t Science Beautiful?

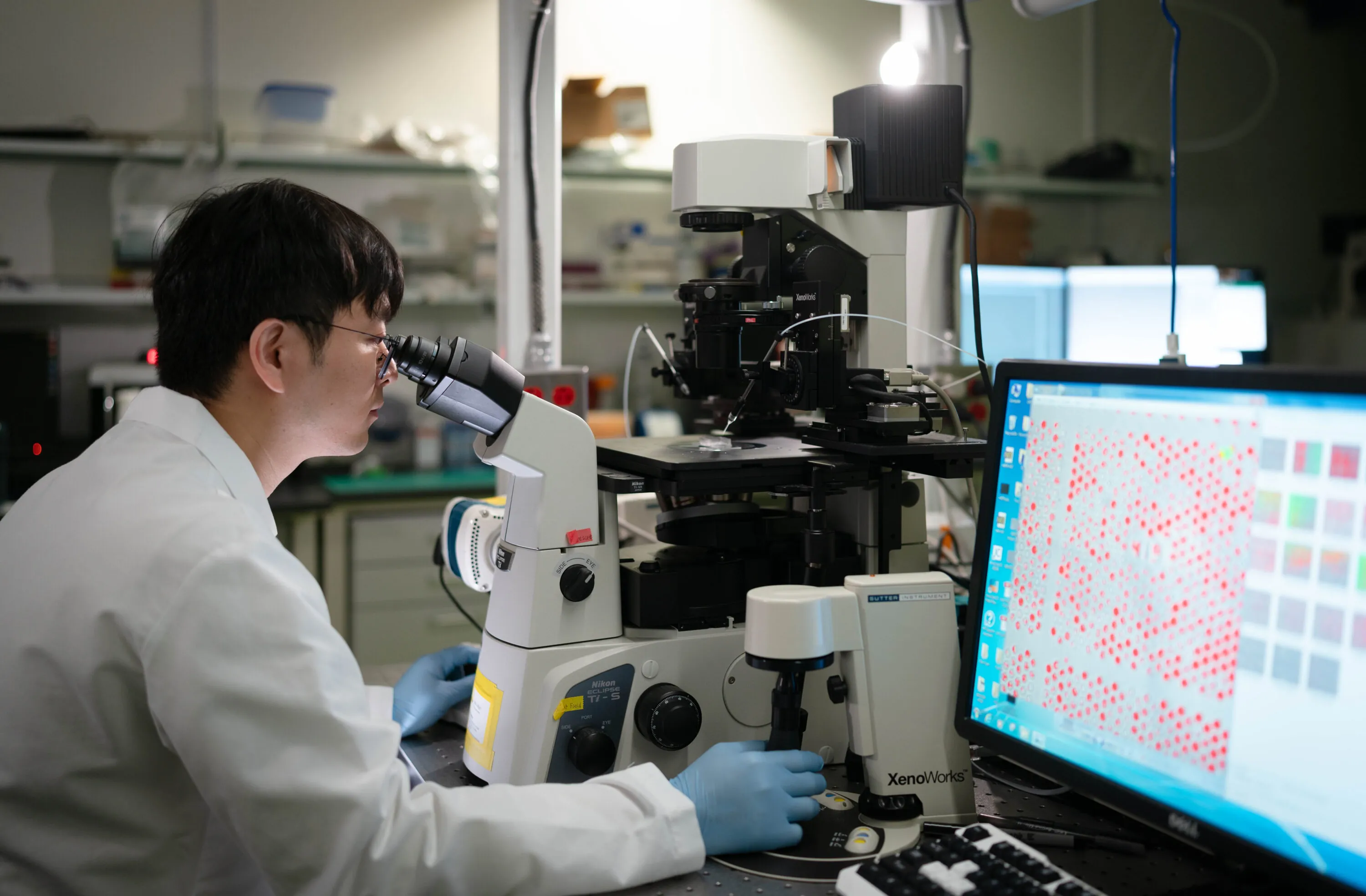

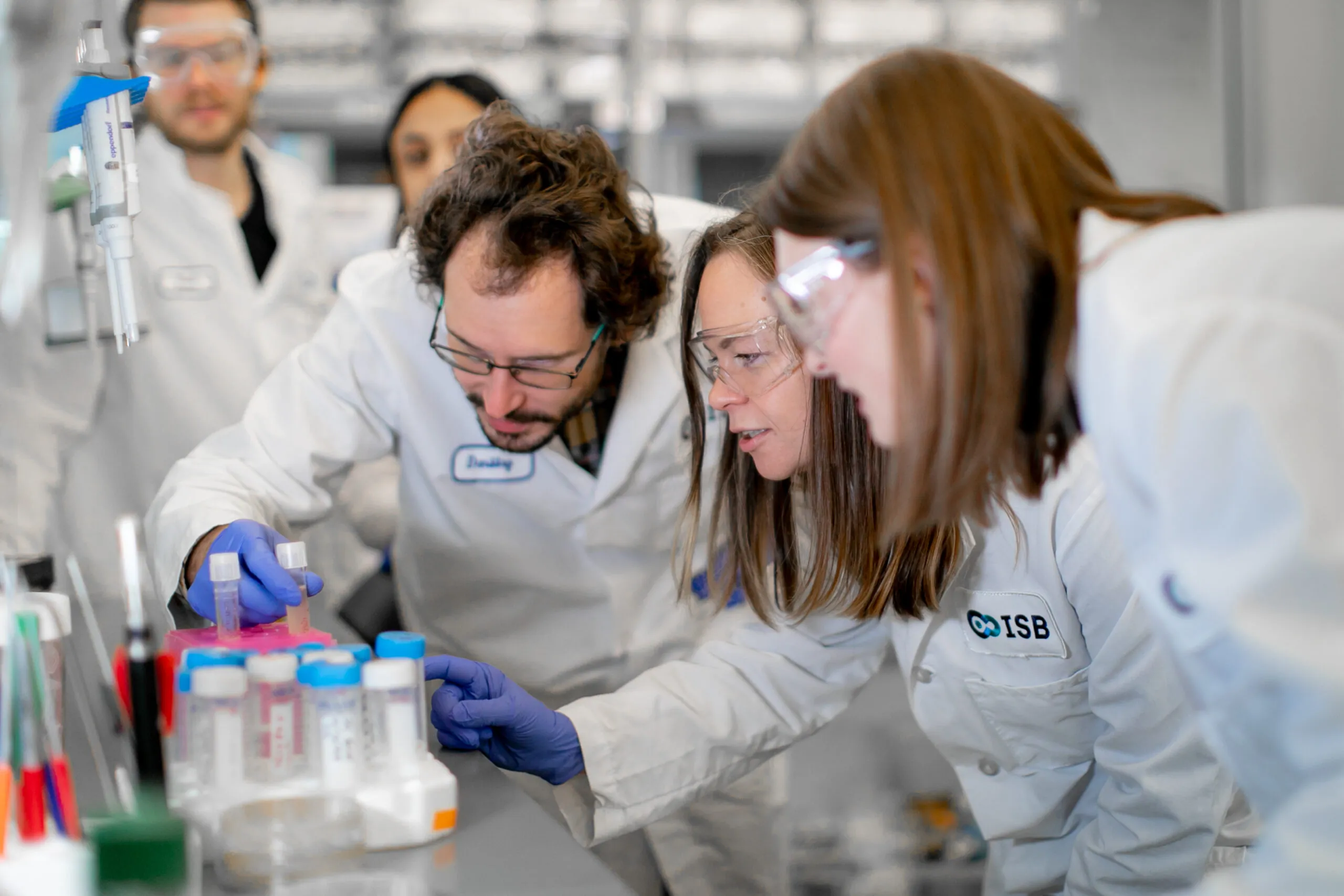

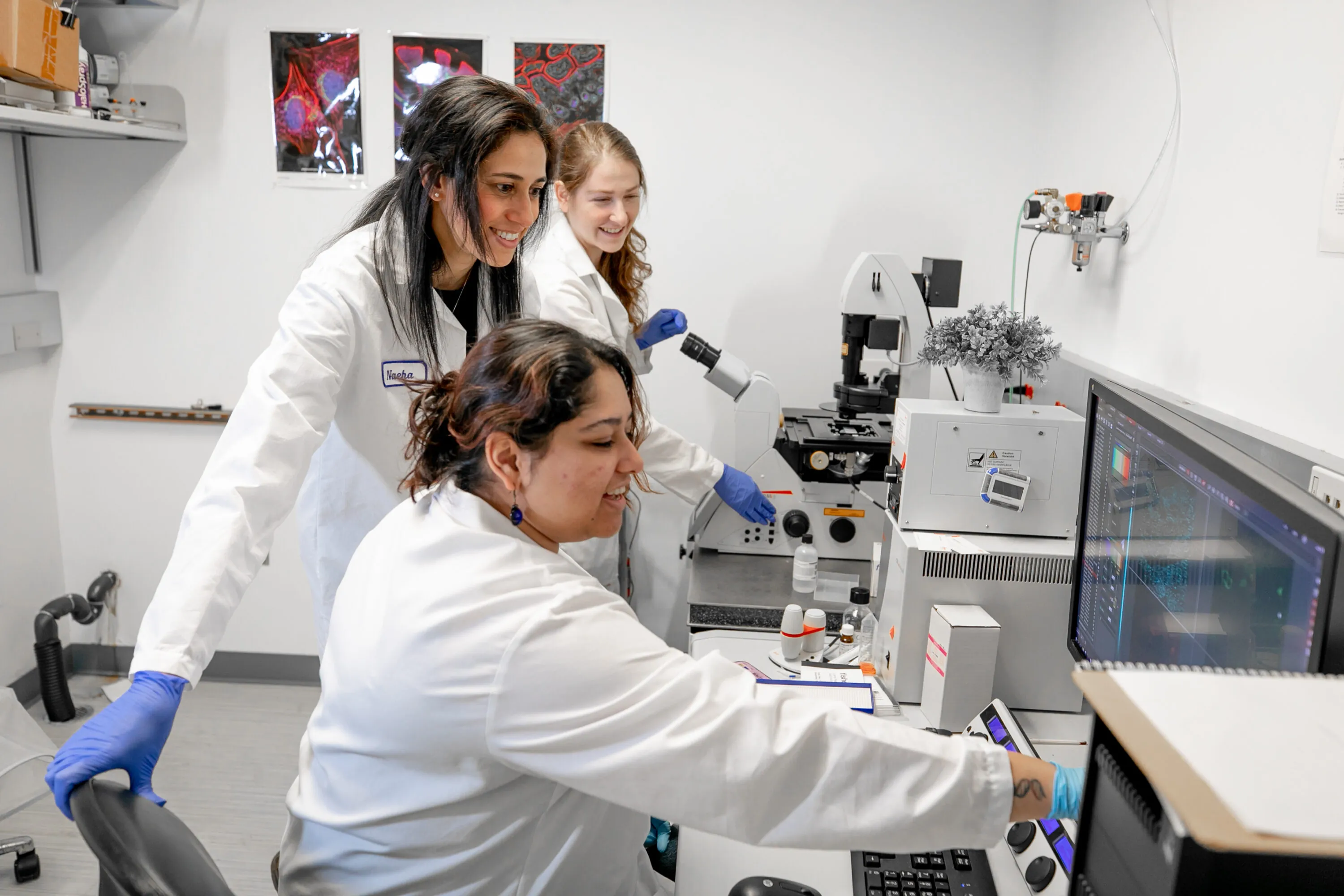

ISB means many things because it does many things. Most research institutes focus on a single area, such as cancer, diabetes, or infectious disease. In contrast, we follow a systems approach, recognizing that biological systems and processes interact and influence one another in complex ways. That’s why our scientists work together in one place — pursuing multiple research paths, exchanging information, and sharing their results freely for the benefit of all. That’s what sets us apart. And this is what it looks like.